Digital Modelling of Knowledge Innovations In Sacrobosco's Sphere: A Practical Application Of CIDOC-CRM And Linked Open Data With CorpusTracer

1. Introduction

In the frame of the research project The Sphere. Knowledge System Evolution and the Shared Scientific Identity of Europe we investigate the knowledge tradition that is interwoven with the history of one text: the Tractatus De Sphaera by Johannes de Sacrobosco. This 13th century treatise on cosmology has been published as part of university textbooks up until the 17th century. We have identified a corpus of more than 300 printed books related to Sacrobosco’s text and obtained digital copies – a process that took three years to complete. These textbooks, which were part of the mandatory curriculum in most European universities at that time, contain Sacrobosco’s text in its original version, as well as in translated, annotated or commented form. In addition, publishers included other texts that were seen as relevant for the study of cosmology from fields such as medicine, astronomy or mathematics (Valleriani, 2017).

Based on this corpus we seek to study how knowledge innovations have proliferated through the dissemination of texts, and identify the structural and social factors that contribute to or hinder the spread of certain kinds of knowledge. We do so by making use of methods from the area of network analysis which we apply on a dataset that we derived from our literary corpus.

This paper presents the foundational work that enables this kind of research with immediate application for similar projects concerned with editorial histories and structural analyses of corpora. We demonstrate the practical application of linked semantic data and the CIDOC-CRM model for shaping and addressing research questions in the humanities (Crofts et al., 2011).

2. Challenges

Our main challenge for this part of the project is the digital representation of the structure of the books and relevant contextual data.

The data model needs to be detailed. Individual texts can be derived from and include other texts. This genealogy of a text needs to be represented. We also require a suitable way of inputting complex data in a user friendly way. We need to be able to query and extend the data in a flexible manner. The data needs to support not only our initial research questions, but also future ones and those by other researchers. We need to be able to maintain an audit trail and trace occurrences that appear as a result of a network analysis to the original source. Last but not least we want to be able to publish our data in an understandable and reusable format.

We meet those challenges by modelling our data in adherence to the formal ontology CIDOC-CRM (Crofts et al., 2011) and the FRBRoo extension for bibliographic records (Bekiari et al., 2015), by storing our data in RDF and according to the 5-star deployment scheme for Linked Open Data (Berners-Lee, 2006), and by making use of the Metaphactory (Metaphacts, n.d.) and ResearchSpace platform for semantic data creation (Oldman, 2016).

The next challenge is the development of a mathematical model that allows us to analyse the evolution of knowledge innovations – initially based on the textual sources and social structures, and later including other kinds of evidence such as book illustrations, family and business relationships, etc.

3. Related work

Our project builds on previous work in the area of semantic data, specifically CIDOC-CRM, and network analysis for research in the humanities.

Historical research that makes use of network modelling and analysis is increasingly relevant (Renn et al., 2016). A recent example is the establishment of the Journal for Historical Network Analysis (Rollinger et al., 2017). The evolution of scientific ideas in particular lends itself to be studied through networks (Lalli and Wintergrün, 2016) as well as how academic funding structures are of influence (Bellotti, 2012).

CIDOC-CRM (Crofts et al., 2011) has been developed and successfully used as a way of reconciling and connecting sources coming from different cultural and technical contexts. Examples include CLAROS (Kurtz et al., 2009), which brings together classical art research databases, PHAROS (Reist et al., 2015), which provides consolidated access to photo archives, or the reconciliation of the Arachne database of the German Archaeological Institute (Krummer, 2006). A RDF implementation of CIDOC-CRM and FRBRoo has been developed at the University of Erlangen (Goerz et al., 2008). The team is also involved in Wiss-Ki (Goerz et al., 2009), along with ResearchSpace (Oldman, 2016) one of few tools that support data creation in CIDOC-CRM compatible RDF (CIDOC/RDF).

4. Our approach

4.1. CorpusTracer

To address the outlined challenges we developed CorpusTracer. CorpusTracer is our front-end for creating and querying the dataset (Figure 1). It is a custom configuration of the Metaphactory semantic data platform and relies on modules developed as part of the ResearchSpace initiative. ResearchSpace is a cultural heritage research platform that builds on Metaphactory as a middleware and introduces modules for CIDOC-CRM compatible data creation and access. It allows to write data directly in CIDOC/RDF to a Blazegraph triple store. Crucially, it is possible to harvest the expressivity of CIDOC-CRM while not having to expose users of the tool to its complexity. We will demonstrate the tool, which is available open-source for download and use.

Figure 1. The home screen of CorpusTracer, featuring a search field and recently edited book and person records, with images and biographical data of persons drawn from Wikidata

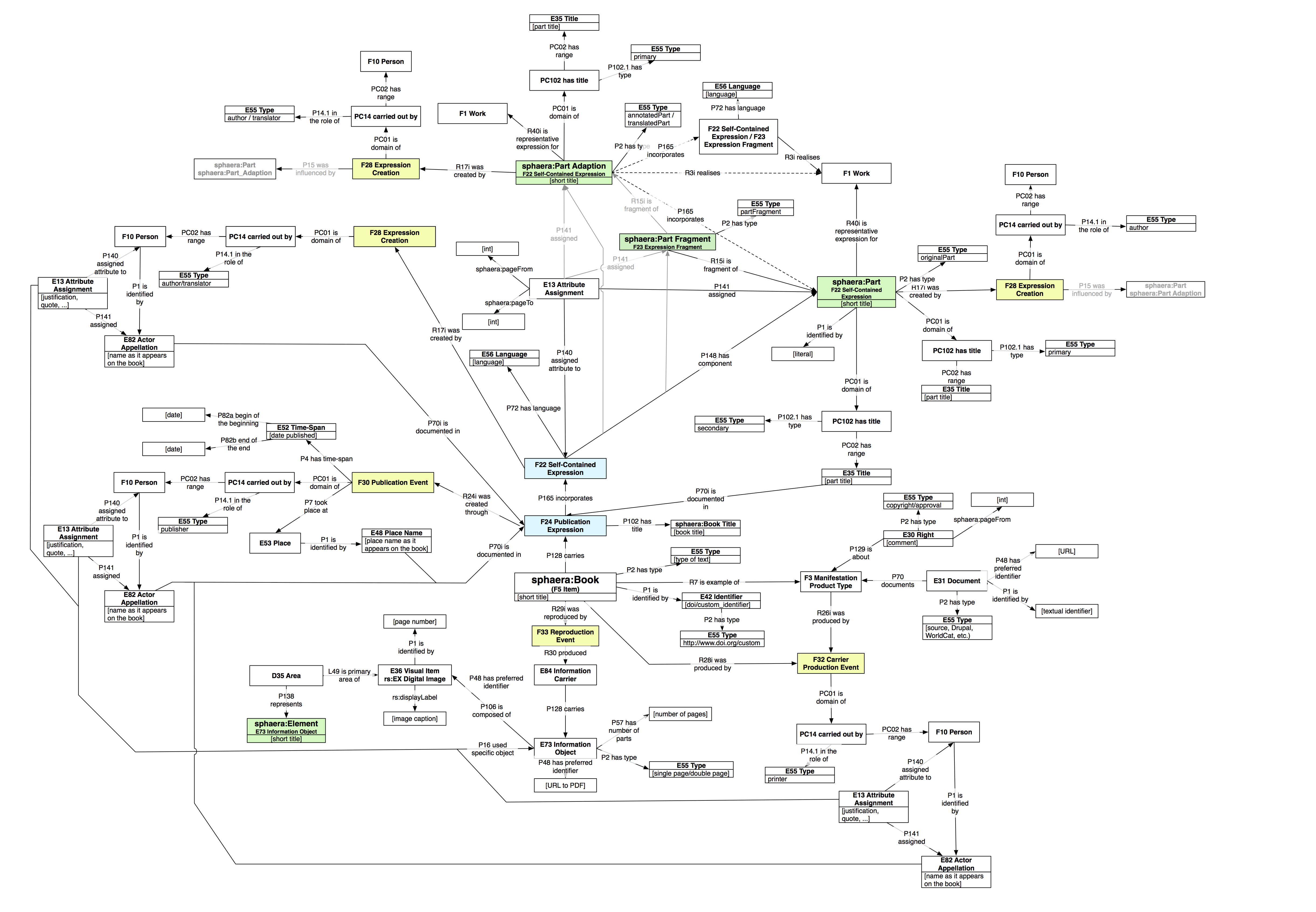

4.2. Data model

Our data model (Figure 2) relies on generic concepts defined in CIDOC-CRM and FRBRoo, making it understandable and reusable outside the scope of our project. We have earlier described the model in more detail (Kräutli and Valleriani, 2017). Since then, we have slightly expanded the model to account for more complex derivations of texts, and for illustrations. The FRBRoo approach, which separates the concept of a book into several layers of physical and conceptual abstractions, fits well to the research framework. 1 It allows us to accurately capture the composition of each book: the texts it contains and, for each text, whether it is an original text or how it derives from existing texts.

We employ a strict separation between the data that is based on our corpus and data that provides context, such as biographical details or location data. We achieve this by linking relevant entities to external sources from Wikidata and the CERL thesaurus. Researchers are able to search for and link to resources on Wikidata directly within the CorpusTracer user interface.

Figure 2. A graphical representation of our CIDOC-CRM/FRBRoo data model

4.3. Discussion

The technical foundation provided through Metaphactory and ResearchSpace allowed us to develop the data model and implement a version of CorpusTracer ready for inputting data within a few months. Our team could then start with inputting the bibliographic data while scholars simultaneously performed the structural analysis of the publications. Changes on both the model and the interface were implemented as we gained a better understanding of the material at hand.

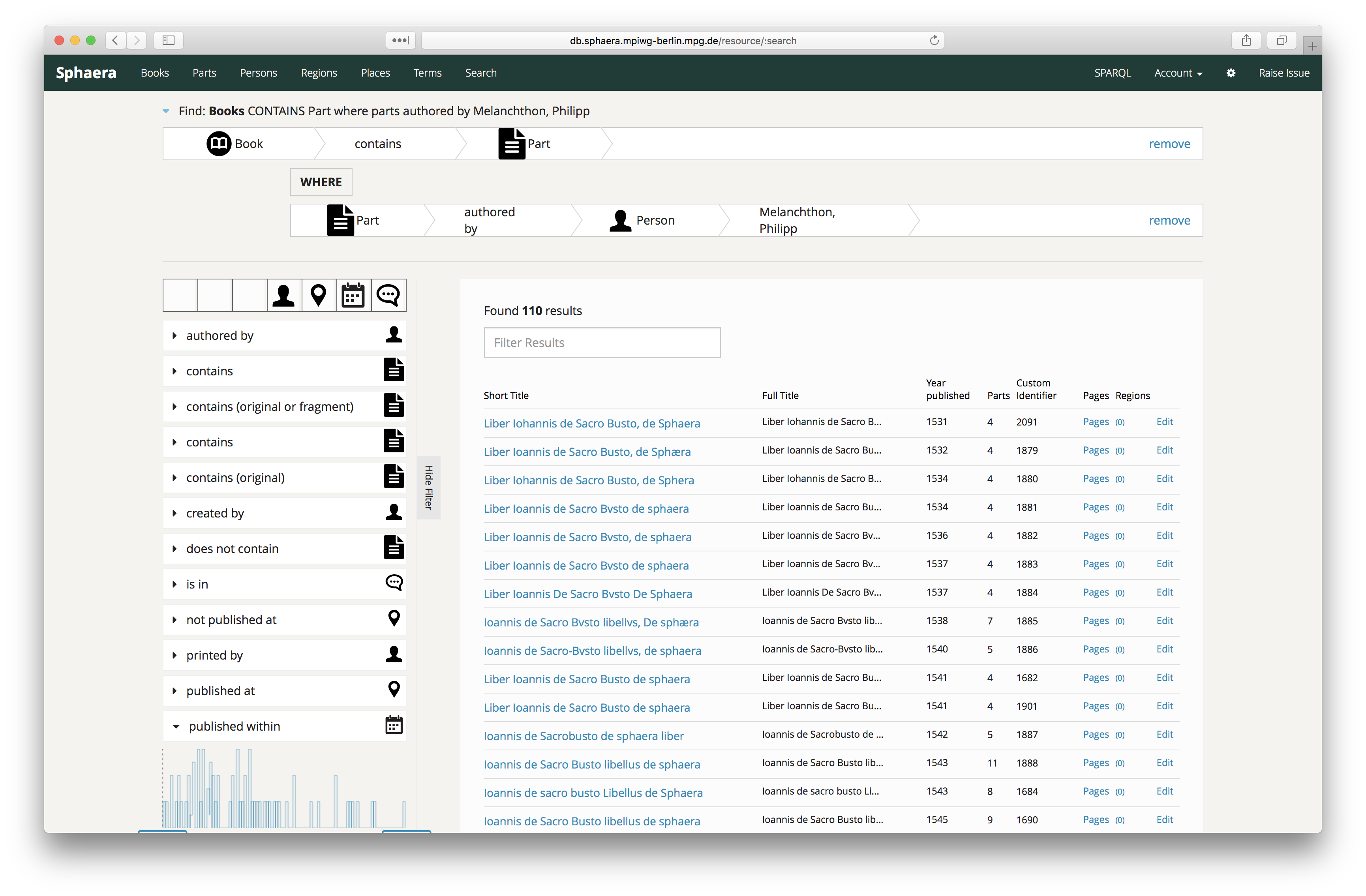

Although we use the platform primarily for data creation, we designed it in a way that will also allow the general public to access and navigate the dataset – which ultimately also benefits expert users. The structured search component of the Metaphacts platform is implemented to allow querying the graph database without having to know the underlying data model (Figure 3). Queries can be made for different entities (books, texts, persons, etc.) and the relationships between them.

Data can be downloaded in CSV format on different pages of the interface as well as by using the structured search. In order to extract the network data required for our analysis we however rely on custom SPARQL queries.

To construct the queries a good knowledge of the data model, the SPARQL syntax and the architecture of graph databases is required. While we found the data created through the platform to be reliable, one has to be careful not to introduce errors when querying the data manually. Unlike in relational databases, where one row in a table corresponds to one item of data, the boundaries of individual entities are not strictly defined in the Blazegraph triple store. We often found errors in our own custom queries that produced a higher number of results than we would have expected.

Despite the above reservations we find it preferable to not to rely on the graphical interface and CSV downloads to access the data, but to use custom SPARQL queries: for reasons of transparency, for maintaining an audit trail between original and extracted data, and for better reproducibility when the dataset changes.

Figure 3. The Structured Search interface of the Metaphacts platform allows

also non-expert users to formulate complex query on the graph database

5. Future

We have now completed the work on the dataset for the structural analysis of the corpus. The dataset can be accessed and downloaded, along with CorpusTracer, via our website (sphaera.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de).

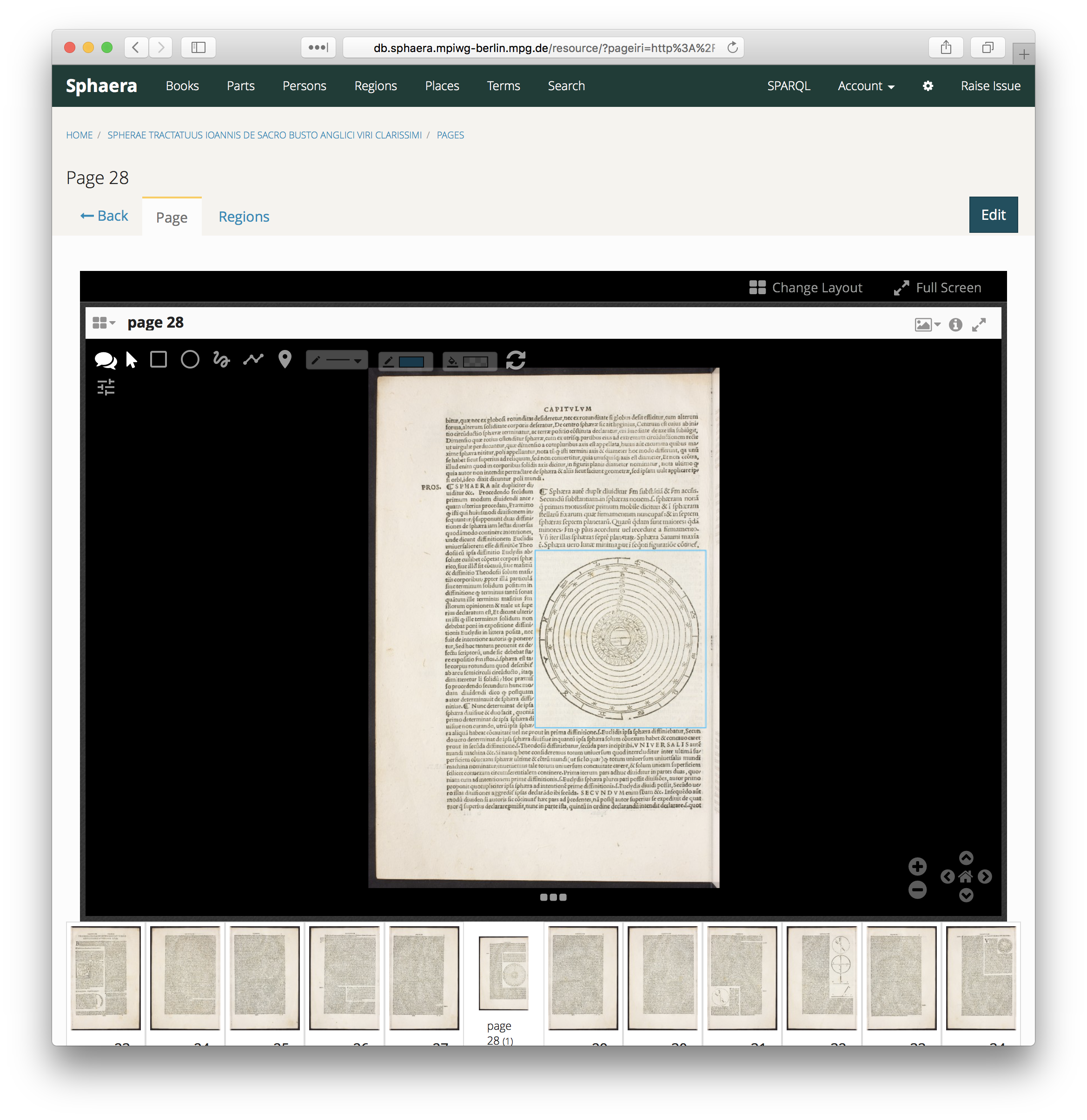

We continue to extend the dataset, particularly with regards to other forms of evidence to study exchange of knowledge. CorpusTracer implements an annotation tool which we use to mark illustrations in the digitised pages of the books (Figure 4). By employing an image hashing algorithm we identify shared illustrations across books that indicate relationships between printers.

Currently we are working on a mathematical model that enables us to identify the contributing structural and social factors that lead to the successful proliferation of particular knowledge innovation.

Figure 4. ResearchSpace provides a Mirador IIIF Viewer with annotation functionality,

which we use to mark illustrations within pages of the books

Appendix A

- Bekiari C., Doerr M., La Boeuf P. and Riva P. (eds.) (2015). Definition of FRBRoo: A Conceptual Model for Bibliographic Information in Object-Oriented Formalism. Retrieved 27 April 2017 from https://www.ifla.org/files/assets/cataloguing/FRBRoo/frbroo_v_2.4.pdf .

- Berners-Lee, T. (2006). Linked Data - Design Issues. Retrieved 23 November 2017, from https://www.w3.org/DesignIssues/LinkedData.html

- Bellotti, E. (2012). Getting funded. Multi-level network of physicists in Italy. Social Networks, 34(2): 215–229. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2011.12.002

- Crofts, N., Doerr, M., Gill, T., Stead, S. and Stiff, M. (eds.). (2011). Definition of the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model. ICOM/CIDOC CRM Special Interest Group.

- Goerz, G., Scholz, M., Merz, D., Krause, S., Fichter, M. and Reinfandt, K. (2009). About WissKI. Retrieved November 22, 2017, from http://wiss-ki.eu/about

- Goerz, G., Schiemann, B. and Oischinger, M. (2008). An implementation of the CIDOC conceptual reference model (4.2.4) in OWL-DL. 2008 Annual Conference of CIDOC, Athens, September 15-18.

- Kräutli, F. and Valleriani, M. (2017). CorpusTracer: A CIDOC database for tracing knowledge networks. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqx047

- Krummer, R. (2006). Integrating data from The Perseus Project and Arachne using the CIDOC CRM An Examination from a Software Developer’s Perspective. Retrieved 22 November 2017, from http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/~rokummer/KummerCIDOC2006.pdf

- Kurtz, D., Parker, G., Shotton, D., Klyne, G., Schroff, F., Zisserman, A. and Wilks, Y. (2009). CLAROS - Bringing Classical Art to a Global Public. Fifth International Conference on e-Science, pp. 20–27. IEEE. http://doi.org/10.1109/e-Science.2009.11

- Lalli, R. and Wintergrün, D. (2016). Building a scientific field in the Post-WWII Era: A network analysis of the renaissance of general relativity. Invited talk at the Forschungskolloquium zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte, Technische Universität, Berlin, 15 June 2016.

- Metaphacts (n.d.). Metaphactory. https://metaphacts.com/product

- Oldman, D. (2016). ResearchSpace. https://public.researchspace.org

- Renn, J., Wintergrün, D., Lalli, R., Laubichler, M. and Valleriani, M. (2016). Netzwerke als Wissensspeicher. In J. Mittelstraß and U. Rüdiger (eds,), Die Zukunft der Wissensspeicher: Forschen, Sammeln und Vermitteln im 21. Jahrhundert. Konstanz: UVK Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, pp. 35–79.

- Reist, I., Farneth, D., Stein, R. S. and Weda, R. (2015). An Introduction to PHAROS: Aggregating Free Access to 31 Million Digitized Images and Counting... Retrieved 22 November 2017, from http://network.icom.museum/fileadmin/user_upload/minisites/cidoc/BoardMeetings/CIDOC_PHAROS_Farneth-Stein-Weda_1.pdf

- Rollinger, C., Düring, M., Gramsch-Stehfest, R. and Stark, M. (eds.). (2017). Journal of Historical Network Research 1. Luxembourg Centre for Conte.mporary and Digital History. https://doi.org/10.25517/jhnr.v1i1.

- Valleriani M. (2017). The tracts of the sphere. Knowledge restructured over a network. In Valleriani M. (ed.), The Structures of Practical Knowledge. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 421–73.

FRBR introduces the concepts of Item, the material book, Manifestation, the prototypical book, Expression, the text of a book, and Work, the overall work conveyed by the book.